I. From Milan to the Middle East: A Brief History of the “Design Week” Phenomenon

Design weeks didn’t begin as festivals. They began as conversations, small, often provincial gatherings where designers, manufacturers, and curious locals attempted to articulate the meaning of “modernity.” Milan in the 1960s turned design into spectacle; London in the early 2000s gave it urban scale; Eindhoven offered the alternative model: design as research ecosystem. Over time, “design week” became both a global ritual and a barometer of cultural confidence. Cities held these events not just to show objects, but to show who they were becoming.

For Tehran, restless, sprawling, perpetually negotiating its own contemporary identity, the need for such a platform has been unmistakable. The city’s design community has long operated in pockets: universities with brilliant but isolated labs, independent studios with avant-garde ambitions, galleries that carry more risk than they can easily sustain. What Tehran Design Week has gradually done is carve a connective tissue across these pockets, giving the designers not only visibility, but a sense of shared momentum.

Tehran Design Week 2025 unfolded across multiple disciplines, product design, fashion, graphics, urban interventions, material innovation, and contemporary crafts, but its strongest and most cohesive pulse emerged from its lighting programme. Light became the event’s interpretive framework, linking heritage and technology, shaping exhibitions, and activating public space. Whether in installations, performances, or cross-disciplinary showcases, lighting served as the principal medium through which designers explored identity, narrative, and spatial experience. This edition positioned illumination not just as a category of design, but as the conceptual backbone of the entire week, making lighting the most defining and critically resonant axis of the 2025 programme.

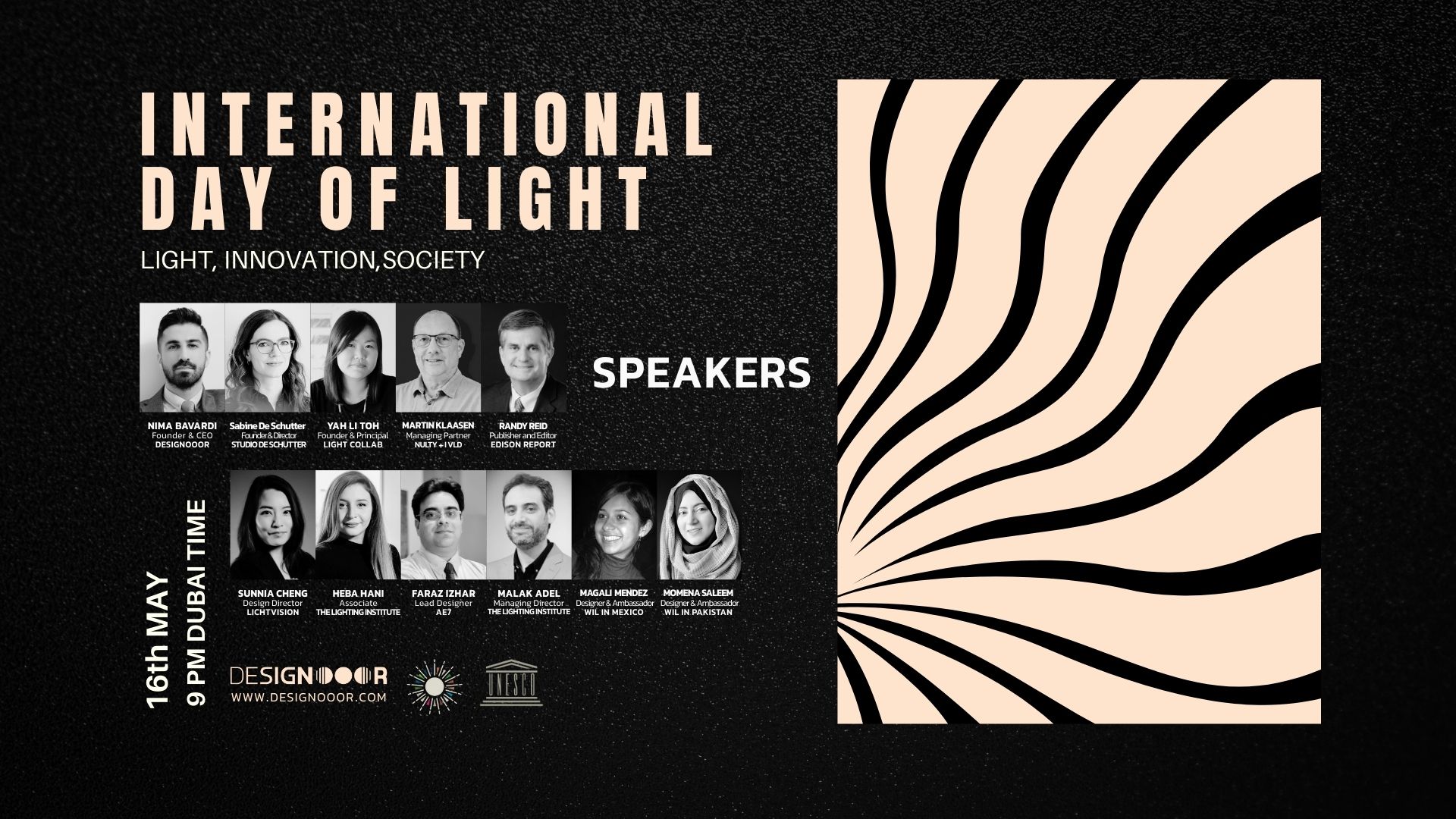

And Designooor’s Media & Academy division curated this luminous map across four sites: University of Tehran, University of Art, Maad Gallery, Berezzi Studio, plus a satellite highlight at the Tehran International Exhibition on Seoul Street.

Why a Cat? The Icon of Tehran Design Week

Iran, in its cultural imagination, is often described as a cat, agile, shapeshifting, present in every corner of daily life. The metaphor reaches back to the Shahnameh, where a tale from the reign of Khosrow Parviz recounts the downfall of the city of Rey after its cats were banished, and its revival only when they returned. The cat becomes a symbol of balance, adaptation, and the fragile ecosystem of urban life.

In Tehran today, cats occupy the streets and courtyards with the same quiet authority. They are decorative and practical, charming and unruly, sometimes a companion, sometimes a complication. Their paradox mirrors the nature of design itself: ubiquitous yet overlooked, playful yet functional, constantly negotiating necessity and desire. In this city, the cat is not only a familiar presence; it is an emblem of persistence, identity, and survival. That is why, for Tehran Design Week, the cat became more than an icon, it became a map, a lens through which design’s role in shaping the city could be understood. Design is the cat of Tehran.

Editor’s Note:

Tehran Design Week, in its latest edition, delivered a rare moment of clarity in one particular field: lighting. The work presented in this segment felt deliberate, contemporary, and, most importantly, anchored in a genuine conversation with global design culture. It was in the shifting colors, measured compositions, and conceptual grounding of the lighting installations that one could sense a maturity taking shape. These works didn’t merely illuminate space; they illuminated possibility.

Yet the strength of the lighting section cast an even sharper light on the rest of the exhibition, sections where coherence weakened, standards became negotiable, and curation seemed guided by something far less principled than design merit. The unevenness wasn’t subtle. It was structural.

Across several halls, the visitor encountered pieces that, by any serious curatorial measure, do not belong in a national design week. Works without conceptual depth, without technical competency, or without any relationship to contemporary discourse appeared beside more serious contributions as if placed there through a gesture of obligation rather than selection. And in Tehran’s tightly knit design community, one hardly needs to look far to understand why: the familiar choreography!

These aren’t small cracks; they are foundational ones.

Editor-in-Chief

II. University of Tehran: The City’s First Luminous Chamber

On the northern edge of its campus, the University of Tehran became the Week’s most atmospheric laboratory. The hallways, ordinary on any other day had been reconfigured into corridors of chromatic intensity.

In the College of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran, Sima Ahvaz (Art Director of the Design Week event at the University of Tehran) with Aidin Arjomand and his team at Linor Lighting worked on the illumination of Contemporary Antiquity, a project by Sima Ahvaz built around a series of painted panels. The premise was elemental: each panel held several layered images, but only one image surfaced at a time, depending on the color of light cast onto it. Under blue light, the blue-rendered illustrations merged seamlessly with the illumination; under green or red, an entirely different image came forward, while the others receded as if erased.

Rather than functioning as an accessory to the artwork, the lighting became the mechanism that activated it. The installation blurred the boundary between painting and illumination, treating light not as a means to reveal a surface but as a force that could rewrite it. In this setup, the artwork didn’t simply change under different lighting conditions, it became a different artwork altogether.

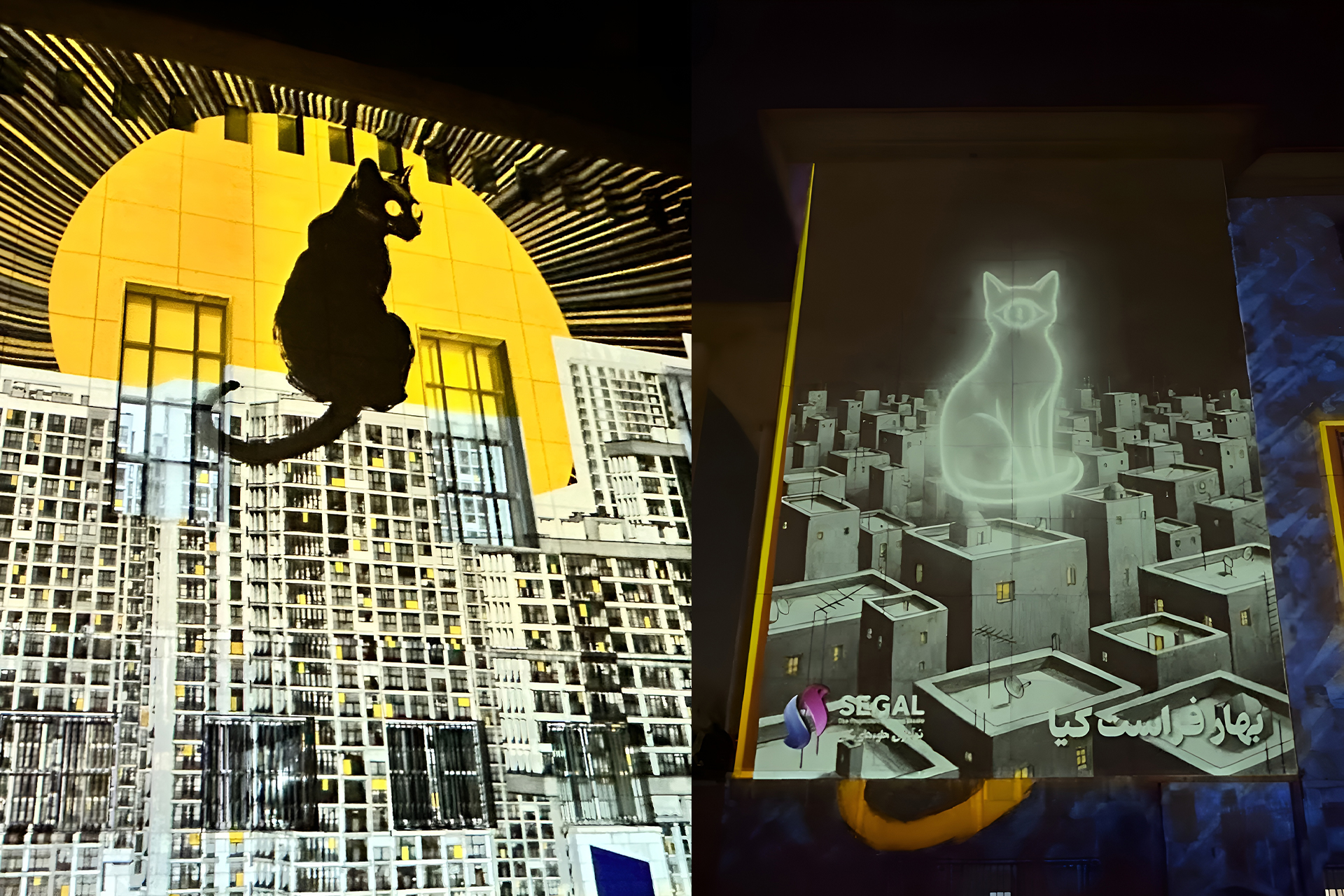

Outside, SEGAL Media transformed the university’s vast architecture into a dynamic canvas. A colossal projection illuminated the exterior of the building, with video mapping breathing life into its cold stone. This was not simply a light show. It was a narrative in flux, a dynamic conversation between light and architecture that reflected the cultural landscape outside.

Within the sea of projections, animated sketches, composed of dozens of hand-painted scenes, came to life, each frame a living memory of stories drawn from the streets of Tehran, its people, and its history. The projection shifted and morphed, merging moments of peaceful domesticity with fleeting fragments of urban life, each one highlighted with the sharp contrast of illuminated and shadows. The installation was less about spectacle and more about presence, creating a moment of reflection beneath the night sky.

In the glow of the projected cat, perched against an expansive sun, it felt like Tehran had just turned the page to a new chapter, one where light itself was no longer something passive, but an active storyteller.

In the central hall stood a stark, declarative installation: a clean, typographic spatial intervention simply titled “Tehran”. Rose Lustre’s work transformed a single word into an architectural object, a threshold through which visitors passed. It was not ornamental; it was territorial, an inscription of the city’s name into the city’s most academic institution.

On the ground floor, circles of light arranged in pulsating rhythms traced pathways across polished surfaces. Designed by Mehrdadfar with Luna Light, the installation worked like a diagram of movement, an illuminated choreography that visualized footsteps before they occurred. The floor became an active participant in guiding bodies through space.

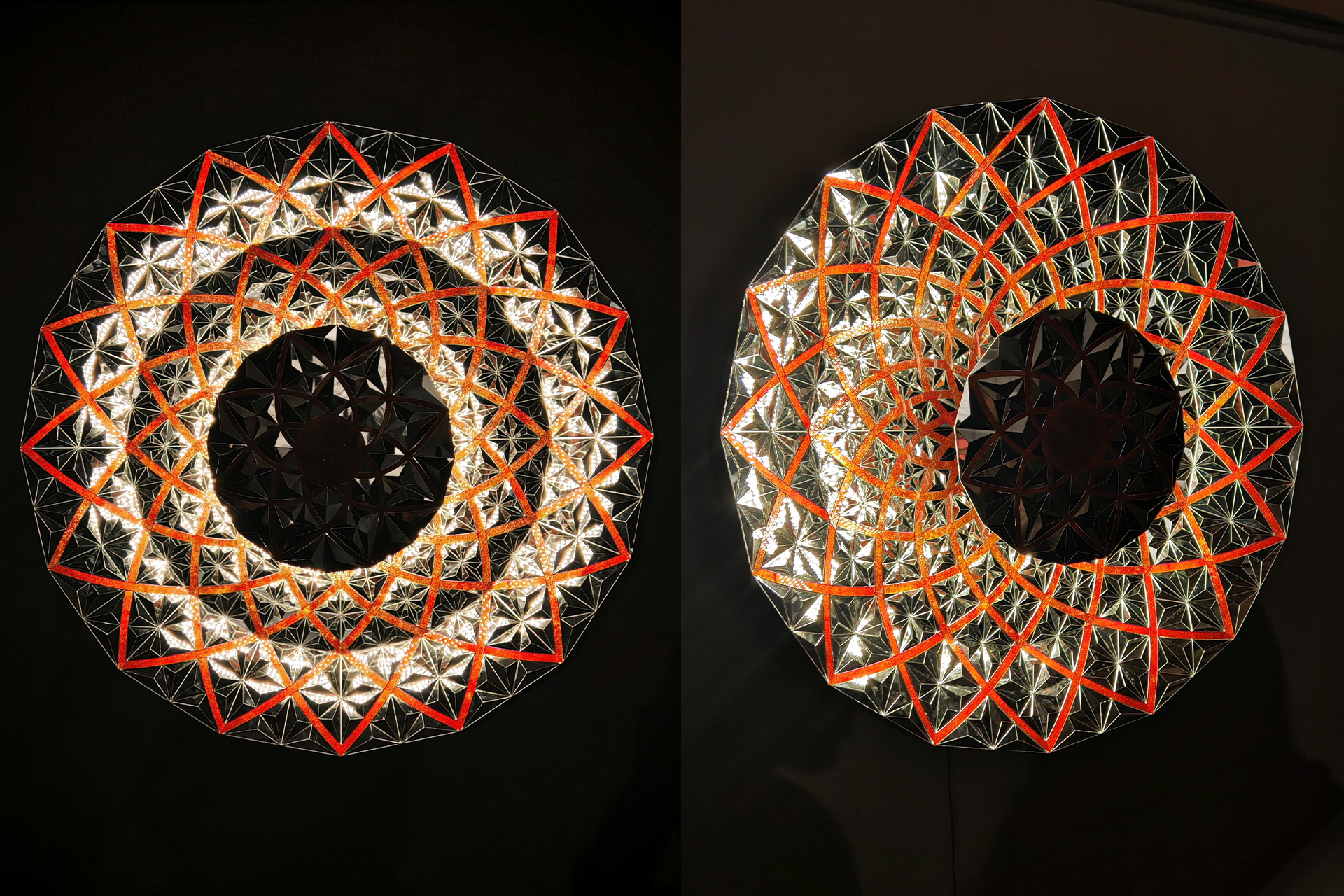

Another standout piece was Hesam Kelay’s luminous mandala, revealing a different kind of structural intelligence. Its symmetry was rigorous, but its energy radiated outward with almost ceremonial intensity. Standing before it felt like encountering a myth translated into circuitry.

Nearby, Jafarnejad’s sculptural object sat quietly on a platform, its golden, orbital form catching stray reflections from the chromatic corridors. It felt planetary, a small celestial body occupying terrestrial space, positioned with the confidence of an archeological artifact transported from a future era. “Jupiter” did not glow, but it seemed to hold light in its surface like memory.

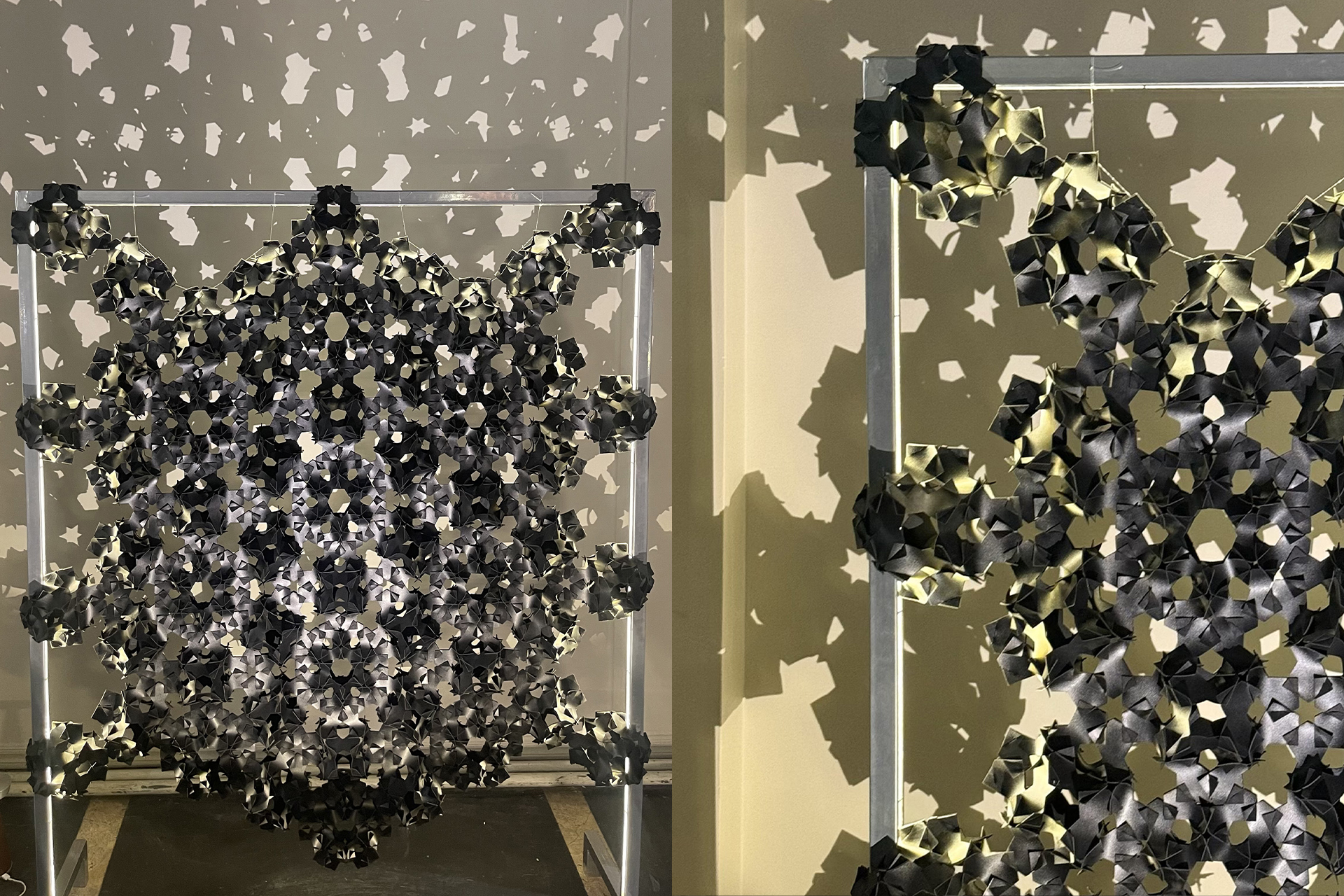

Geolock, designed by Maryam Hosseini and Shayan Rakhshan, uses an interlocking system of leather and metal to form a structural skin that needs no stitching or fasteners. Its geometry emerges piece by piece, following a part-to-whole logic familiar to Iranian ornamental design. Under the linear light embedded in its frame, the pattern doesn’t simply illuminate; it projects a secondary composition onto the wall, where shadows expand into a tessellated field that feels both architectural and quietly atmospheric.

The density of the modules shifts across the surface, creating varying degrees of transparency that allow light to slip through in controlled gradients. As a result, the partition functions less as a divider and more as a device for shaping light, producing a rhythm of brightness and shadow that gives the space a subtle, evolving texture.

Keley’s Eye didn’t demand attention so much as interrupt the visual noise around it. A circular light-form, neither dramatic nor understated, it sat in a zone of its own, quiet, steady, and deliberately unadorned.

Taken together, the works at the University of Tehran formed a study in spatial psychology. They suggested not just what light can do, but what light can make you feel, how it can alter the calibration of time inside a room.

III. Tehran International Exhibition, Seoul Street: Bavardi’s Other Creature

Bamboo by Nima Bavardi stood out in the Tehran International Exhibition largely because it resisted the common temptation of over-designed “statement pieces.” The work borrowed the structural logic of bamboo, not as an exotic reference, but as a functional template: repetition, vertical tension, and a sense of modular growth. Instead of relying on ornamental complexity, Bavardi leaned into proportion and rhythm, letting the form build itself through a consistent geometric language.

What made the piece effective was its clarity. In a hall crowded with objects trying to announce themselves, Bamboo maintained a kind of discipline. The surfaces were clean, the material choices direct, and the transitions between elements intentional rather than showy. Even its interaction with light, subtle, not performative, gave the work a grounded presence that many neighboring projects lacked. It was less about creating a spectacle and more about demonstrating control over form, scale, and spatial responsibility.

If the exhibition had a handful of works that felt resolved, works that understood where to stop, Bamboo was one of them. It didn’t try to transform the space; it simply held it well.

IV. University of Art: A Single Voice with Galactic Scale

In contrast to the multiplicity of the Tehran campus, the University of Art offered a single, commanding presence.

Saraf’s installation, drawing on the intertwined languages of Persian domes, mathematical geometry, and galactic orbits, stood like a luminous hypothesis. Suspended arcs, concentric halos, and orbital lines created an architecture of light that echoed both ancient cosmologies and contemporary astrophysics. The geometry was rigorous, yet the atmosphere was spiritual. Standing beneath it, one felt the gravitational pull of a structure that understood both the heavens and the mathematics by which we attempt to describe them.

It was the rare piece that felt simultaneously monumental and weightless, an equilibrium achieved only when an artist understands her references so deeply that the resulting work transcends them.

V. Light as Method: Four Studies from Berezzi Studio

Berezzi Studio, known for its willingness to house risk, offered a trio of works that approached light as a structural force.

1.Ali Asadbeigi – Installation, 2.Sepehr Mehrdadfar x Modnoor -“Roch Light”, 3.Nima Bavardi x Waxy – “Kangar” | Location: Berezzi Studio | Video © Elahe Nikoo

Ali Asadbeigi – Installation

Asadbeigi’s installation centered on a single garment suspended like a quiet emblem of the Iranian woman. Around it, a ring of crystal elements caught and fractured the light, multiplying the figure into a constellation of reflections that stretched from ceiling to floor. Even the shards embedded in the ground played a role: they mirrored back an image disrupted, suggesting the fractures, pressures, and negotiations that shape a woman’s public life in contemporary Iran. What might have been merely symbolic became spatial; the viewer didn’t just observe the piece, they stood inside its tension, inside the distance between the ideal and the lived reality.

Sepehr Mehrdadfar x Modnoor – “Roch Light”

Roch, named after the Pahlavi word for light, operates less as a fixture and more as a sculptural stance within space. Its form is assertive without theatrics, fluid, deliberate, and designed to occupy a room with a kind of architectural confidence. The piece treats illumination as a spatial event: light becomes a way of outlining presence rather than merely providing visibility. In Roch, brightness is secondary to attitude. It shifts the atmosphere by shaping how the surrounding volume is perceived, turning a simple act of lighting into an encounter with form, density, and intent. Produced and presented by Modnoor Light, the work positions itself squarely at the intersection of object and environment, where the experience of space begins with the thing that interrupts it.

Nima Bavardi x Waxy – “Kangar”

tudio presented the “Kangar” Table Lamp, designed by Nima Bavardi. Inspired by the Kangar plants found in regions such as Ethiopia, South America, and the mountains of Iran, which symbolize resilience and growth in challenging environments, this collection embodies a fusion of natural beauty and contemporary design.

This collection exemplifies biophilic design, aiming to integrate natural elements into contemporary living environments. With this work, Waxy Design Studio demonstrates how design can bridge the gap between the natural world and human-made spaces, providing an emotional and meaningful experience for users.

Afsoon Habibi’s “Gireh” is a modular lighting design that blends simplicity with adaptability. Installed at Berezzi Studio, it allows the user to adjust the light’s direction and intensity, offering flexibility for various environments. Rather than a static object, it becomes a tool, where light can be controlled in a way that responds to the needs of the space. “Gireh” doesn’t overcomplicate; it’s about giving the user subtle control over the lighting, allowing it to shape the mood without overwhelming the room.

VI. Maad Gallery: Performance as Illumination

Maad Gallery became the Week’s most intimate stage.

Rad’s piece dissolved the boundaries between fashion, product display, and lighting by staging the audience inside a choreographed atmosphere. The moment each lid was lifted, timed with the crystalline rise of the soundtrack, the gallery shifted into a luminous field shaped by rotating reflections, suspended haze, and precise gestures. Light didn’t illuminate the jewelry; it activated it, turning each object into a prompt for perception. The performers’ measured catwalk became a vector for the gaze, guiding attention through a field where vapor, metal, and fabric interacted as equal agents.

The “fashion bite” completed the cycle, transforming the viewer from a passive spectator into a co-author. Every brand’s object, served like a course in a tasting menu, gained a new temporality: a moment where light choreographed not desire but awareness. In a festival dominated by static installations, Rad demonstrated that lighting is not a backdrop. It is a system of meaning, one that can reorganize how bodies, products, and images meet inside a single, precise moment of visibility.

VII. A City Learning to Speak in Light

Across these locations, Tehran Design Week revealed a city in the midst of aesthetic self-definition. The works suggested a culture comfortable with complexity, eager for experimentation, and unafraid of scale, whether cosmic, architectural, or intimately human.

Light, in this context, became Tehran’s unofficial language. It offered clarity where the city is often chaotic, softness where it is hard-edged, direction where it is uncertain. More importantly, it offered possibility.

For one week, Tehran was illuminated not by its streetlights but by ideas, rooms that glowed blue, halls that pulsed, floors that charted movement, domes made of orbits, and creatures of bamboo rising in the night.

Design Week did not show the city as it is.

It showed the city as it might become.