Editor’s Note:

Manar Abu Dhabi has entered its second edition with a clarity that feels both ancient and strangely futuristic. As light artists converge across the Emirates, what emerges is not a festival of spectacle but a study in how illumination behaves when it is stripped of extravagance and asked to listen instead of announce. What follows is an extended reflection on that shift, tracing the lineage of light-based art from its earliest impulses to its current presence across Jubail Island, Souq Al Mina, and the oases of Al Ain. For Designooor’s readers, practitioners, and students, this is not coverage; it is a field lesson in how light can transform a landscape, a body, and a way of thinking.

Hamed Mahzoon

I. THE COMPASS RESTORED:

Manar Abu Dhabi 2025 and the New Geography of Light

Public light art has been haunted by its own origin story for more than a century. Before it claimed plazas and waterfronts, before it was wrapped in the language of installation and immersion, it lived in the residual glow of two parallel histories: ritual and technology. Humanity’s earliest light works were not designed; they were observed. A torch raised in a cave, a fire flickering against stone, the spectral proximity of dawn on a horizon, these were the first experiments in illumination as narrative. The world’s earliest civilizations learned to read the sky long before they learned to draw it, treating starlight as a navigational scripture.

Modernity, naturally, disrupted this ancient literacy. In the 19th century, when the invention of electric lighting turned cities into radiant laboratories, artists began borrowing from the new circuitry of the industrial age. By the early 20th century, Russian Constructivists, Italian Futurists, and Bauhaus designers had folded light into an evolving vocabulary of motion and abstraction. Neon was no longer a sign but a gesture. Lasers, LEDs, and projection technologies turned illumination into a material capable of carrying symbolism, memory, or critique.

Yet the escape from spectacle has always been elusive. When public light art became a global phenomenon in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, it often leaned toward maximalism. Festivals traded in hyper-saturated color, monumental projections, and choreographed displays designed for cameras more than for bodies. What one gained in visibility, one frequently lost in intimacy. The artistry was real; the subtlety less so.

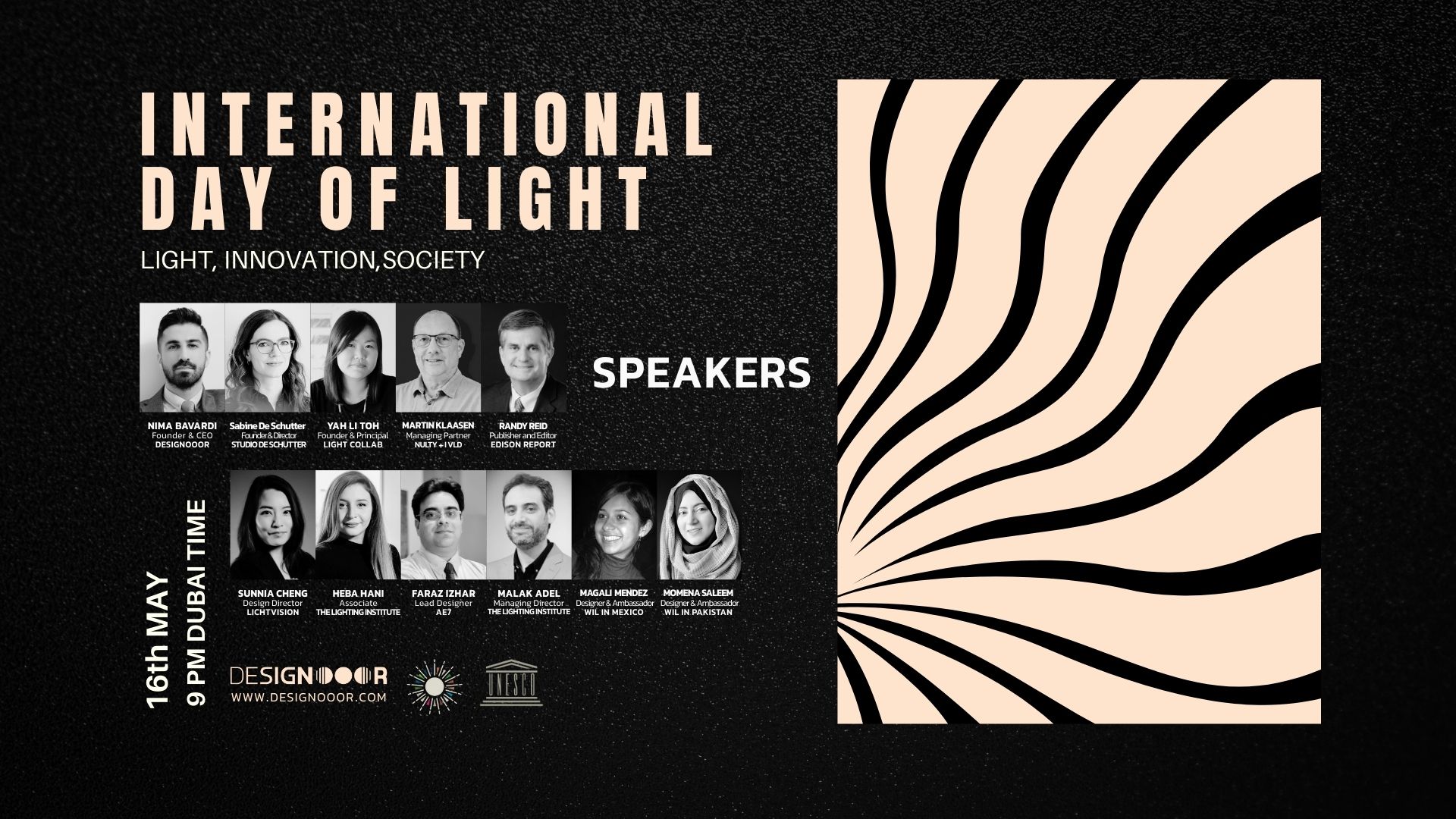

Manar Abu Dhabi 2025 arrives as an intervention in that trajectory. It proposes that light can be encountered the way a cartographer handles paper, the way a navigator reads a changing sea. Under the curatorial direction of Khai Hori, with Alia Zaal Lootah, Munira Al Sayegh, and Mariam Alshehhi shaping its conceptual compass, the exhibition distributes twenty-three works across four sites that operate like four states of mind: the oases of Al Qattara and Al Jimi, the mangrove world of Jubail Island, and the industrial waterfront of Mina Zayed. Each location holds a memory, and each artwork responds not to the spectacle of illumination but to its temperament.

The Return of Orientation

The curatorial framework, “The Light Compass,” is built on a deceptively simple proposition: light is not decoration, it is direction. Across the Gulf’s history, illumination was a form of navigation. The annual rise of Suhail marked the easing of unbearable heat. Moonlight revealed safe routes across desert and sea. Even the shimmer of sand under starlight signaled shifts in wind and terrain. Light was a companion, not a performance.

This lineage circulates through the exhibition like an undercurrent. Instead of dazzling from afar, many works sit low, breathe softly, or occupy liminal ground. They invite movement rather than submission. They suggest that orientation is not a fixed act but a dialogue between the body and its surroundings.

II. Jubail Island: Light in a Landscape of Quiet Motion

Jubail’s mangroves form a landscape that resists exaggeration. Light here must earn its place, and the selected artists respond with restraint and precision.

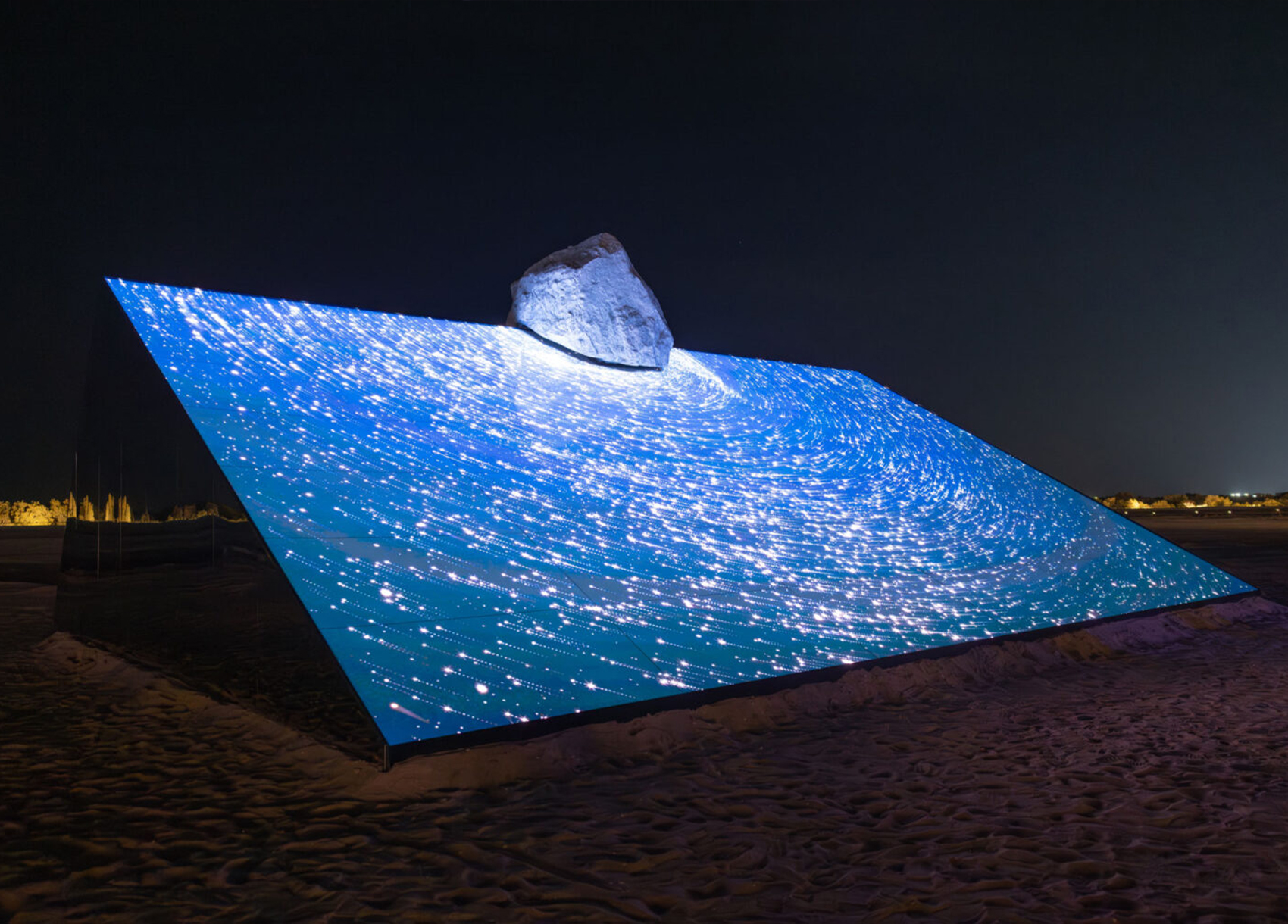

Skyward, by Ezequiel Pini, composes a mirrored incline that folds the night sky inward, granting visitors a view that is neither celestial nor terrestrial but something in between. The reflective surface acts like a hinge between worlds. A balanced stone placed alongside the plane echoes the ritual of grounding, turning the work into a study of how the horizon can be rearranged. The installation’s minimalism does not simplify; it concentrates. It treats the sky as memory and the reflection as a method for returning to it.

Nearby, Whispers by DRIFT inhabits a crescent-shaped dune. The piece feels almost borrowed from the natural world, as illuminated filaments sway with the breeze, transforming the area into a field of responsive luminescence. From above, the work appears like a soft constellation collapsed to earth. Walking through it, however, one becomes part of its choreography. The dune breathes, and for a moment, the visitor does too.

Lachlan Turczan’s Veil I introduces precision where DRIFT introduces softness. Programmable laser planes cut through night air with calibrated movement. The work functions like an atmospheric instrument, shaping space through the barest of lines. Light becomes surface, then dissolves. The effect is meditative without surrendering its technical rigour. Turczan’s planes recall an old navigational habit: finding orientation not by mass but by glimmer.

Shaikha Al Mazrou’s Contingent Object takes an opposite approach. The artwork is not a beam but a field: a crystalline salt circle that undergoes slow, visible transformation through evaporation and time. At night, a soft perimeter of light turns the installation into a moon-like disc resting on the ground. It is fragile and precise, luminous and perishable, an alchemical reminder that illumination need not be instantaneous to be powerful.

III. Al Ain: Breath, Memory, and the Trees That Listen

In the oases of Al Qattara and Al Jimi, light moves differently. It doesn’t cut; it glows. It doesn’t command; it listens.

Breath of the Same Place, by Maitha Hamdan, centers on a ghaf tree whose canopy holds strands of light that respond to the presence of nearby bodies. In a region where the ghaf symbolizes resilience and continuity, this responsive structure carries emotional weight. As visitors approach, the light shifts, suggesting that presence is not simply a matter of being seen but of being sensed. Along the path, ribbons catch both wind and illumination, establishing a slow rhythm between movement and stillness. If Jubail’s works invoke navigational clarity, Hamdan’s work restores the idea that orientation begins with shared breath.

IV. The Port as Memory Device

In Souq Al Mina, light collides with history rather than landscape. The waterfront’s industrial skeleton becomes a stage for contemporary reflection.

KAWS’s Holiday Abu Dhabi introduces a monumental reclining figure holding a glowing celestial sphere. The gesture creates a triad between sculpture, moon, and harbour. Mariners once read this coastline by the light of the sky; here a figure reads the sky by holding it. The distinction is slight but transformative. The port finally glows in reply.

Nearby, Alcove Ltd by Encor Studio transforms a recycled shipping container into a chamber of refracted light and sound. What appears industrial from the outside becomes sensorially complex within. Bodies trigger shifts in the environment. Mist blurs the edges of perception. The container, once a symbol of circulation and goods, becomes a container of attention instead.

V. The Digital as Landscape

Finally, As Water Falls by Iregular positions itself in a lineage of interactive digital works that treat nature not as metaphor but as collaborator. The waterfall’s patterns, responsive to touch, reveal the mutability of both water and image. The piece never repeats itself, offering a reminder that interactivity should not be synonymous with novelty; it should be synonymous with change.

VI. Toward a Vocabulary of Attunement

Taken together, the eight highlighted works selected by Designooor present a shift in public light art: away from the bold and toward the attentive. In the context of Abu Dhabi, this shift feels particularly resonant. The region’s navigational traditions once relied on reading minimal signals across vast spaces. Manar Abu Dhabi 2025 recovers that sensitivity using contemporary tools. Light becomes not spectacle but syntax. It acts as an instrument for alignment, reflection, and recalibration.

If early civilizations learned to read the heavens in order to understand where they stood, this exhibition suggests something related yet distinct: that orientation is not only a matter of direction but of relation. The compass points outward but begins inward. Each beam, shimmer, or quiet pulse unveils a geography of presence, teaching visitors how to move through the world with greater attention.

In that sense, the light that once led travelers home assumes a new task. It guides us not across oceans or deserts, but across perception itself.