Walking on Melting Light

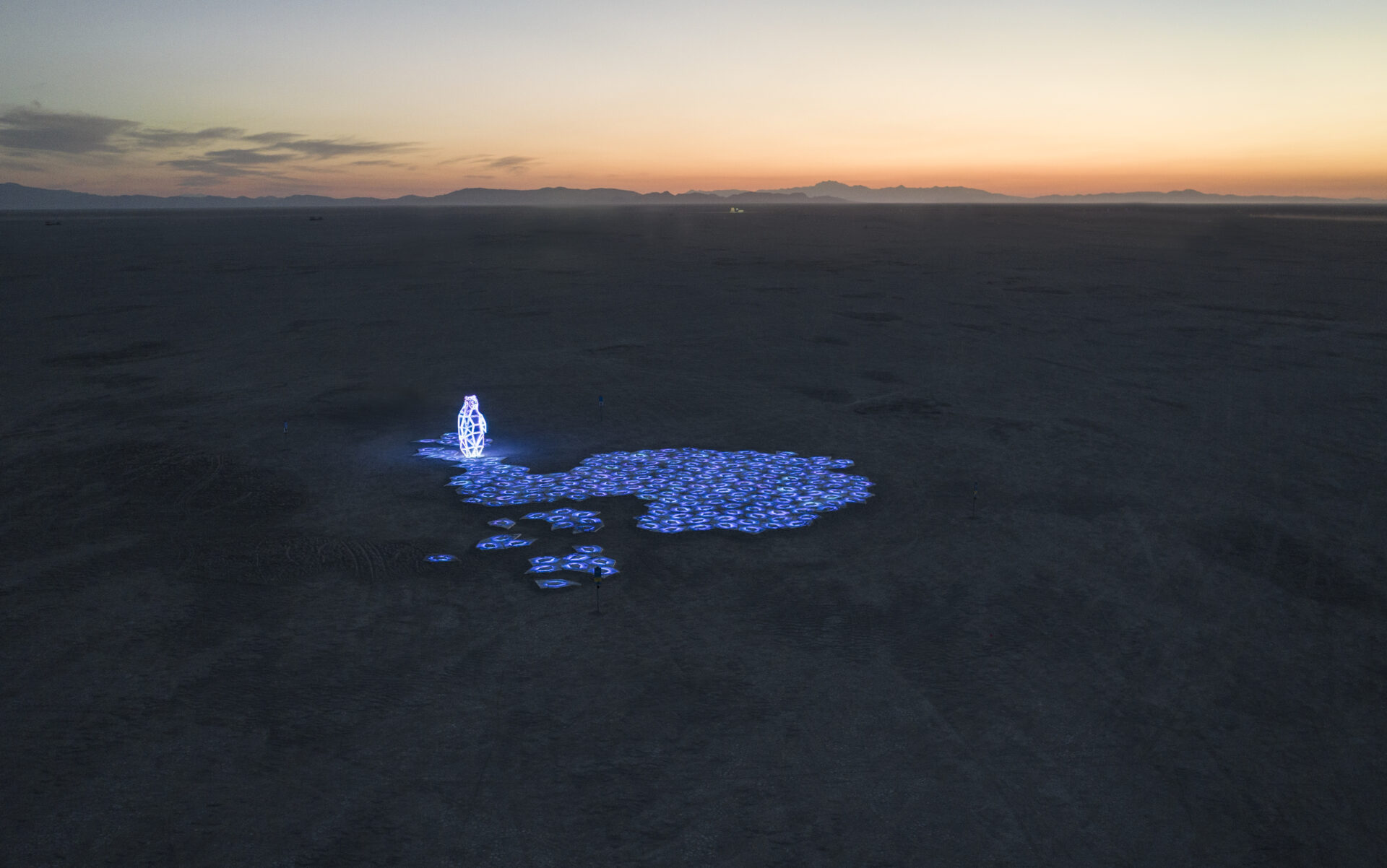

Jen Lewin, an artist-engineer who makes light installations you can actually play, created The Last Ocean, a giant walkable “ice field” that first appeared at Burning Man in 2022 as a Black Rock City Honoraria project, and then moved into the everyday world through public showings like Beacon Park in Detroit in 2022. Made from reclaimed ocean and ocean-bound plastic, it turns discarded material into something glowing and strangely beautiful, an environmental warning that doesn’t feel like a lecture, because it only fully comes alive when people step into it.

Lewin’s starting point with The Last Ocean isn’t “how do I make a beautiful light piece?”, it’s a more unsettling question: how do you get people to feel an ecological crisis that is statistically enormous but emotionally remote? The problem is distance: melting ice shelves and collapsing ecosystems happen “out there,” far from the body. So she uses what light does best, turning something abstract into something immediate. The installation behaves like ice under pressure: it wakes up when you arrive, it reacts when you move, it makes you aware of your footprint without scolding you. The invitation is playful, but the challenge underneath is serious: can light carry urgency gently enough that people stay, and clearly enough that they remember?

For Lewin, the answer is basically yes, if the light behaves like a relationship, not a billboard. In The Last Ocean, the illumination isn’t “added on” to communicate an idea; it is the communication. You move, the field responds. You pause, it shifts. The glow spreads and fades like a living system, so people learn through cause-and-effect rather than explanation. And Lewin says the quiet part out loud when she describes the sculpture as something that’s truly “played with”, because play is the hook that keeps you present long enough for meaning to land.

What The Last Ocean does in the world is sneaky and kind of brilliant: it gets the body first, and the conscience second. People don’t approach it like a typical “message artwork.” They step onto it, test it, dance on it, do yoga on it, chase the ripples with friends, and without noticing the exact moment it happens, they become part of the light system. Suddenly, the crowd turns into a shared choreography: waves of light that only exist because someone moved. That’s the emotional pivot. Climate anxiety stops being a distant headline and becomes a felt experience of connection, cause, and consequence, something you can literally watch traveling outward from your own steps.

After its first launch, the piece kept moving, reappearing in different public settings where new audiences could activate it and generate new “wave patterns” of use and meaning. Each site changes the mood a little: sometimes it reads like a spectacle, sometimes like a public commons. But the core gesture stays the same, people make the light, and the light makes the moment.