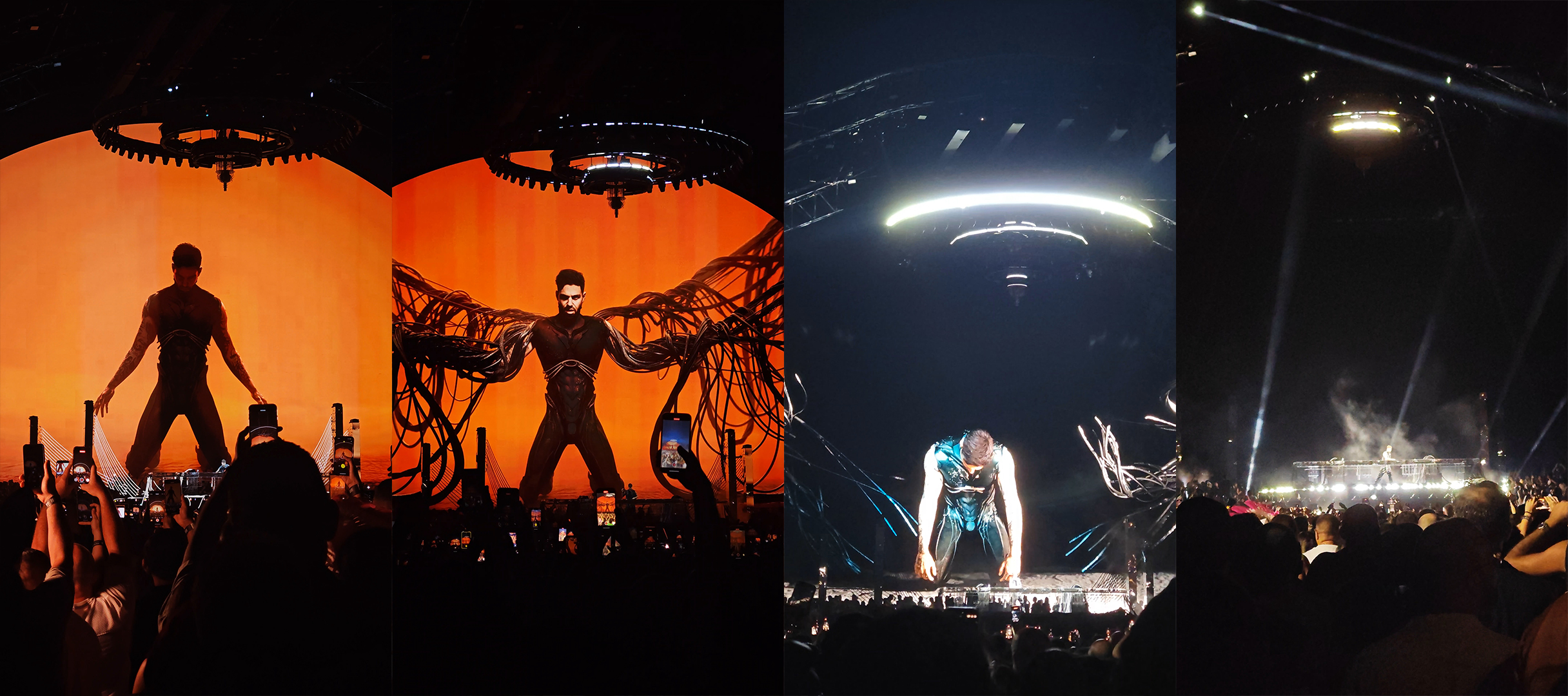

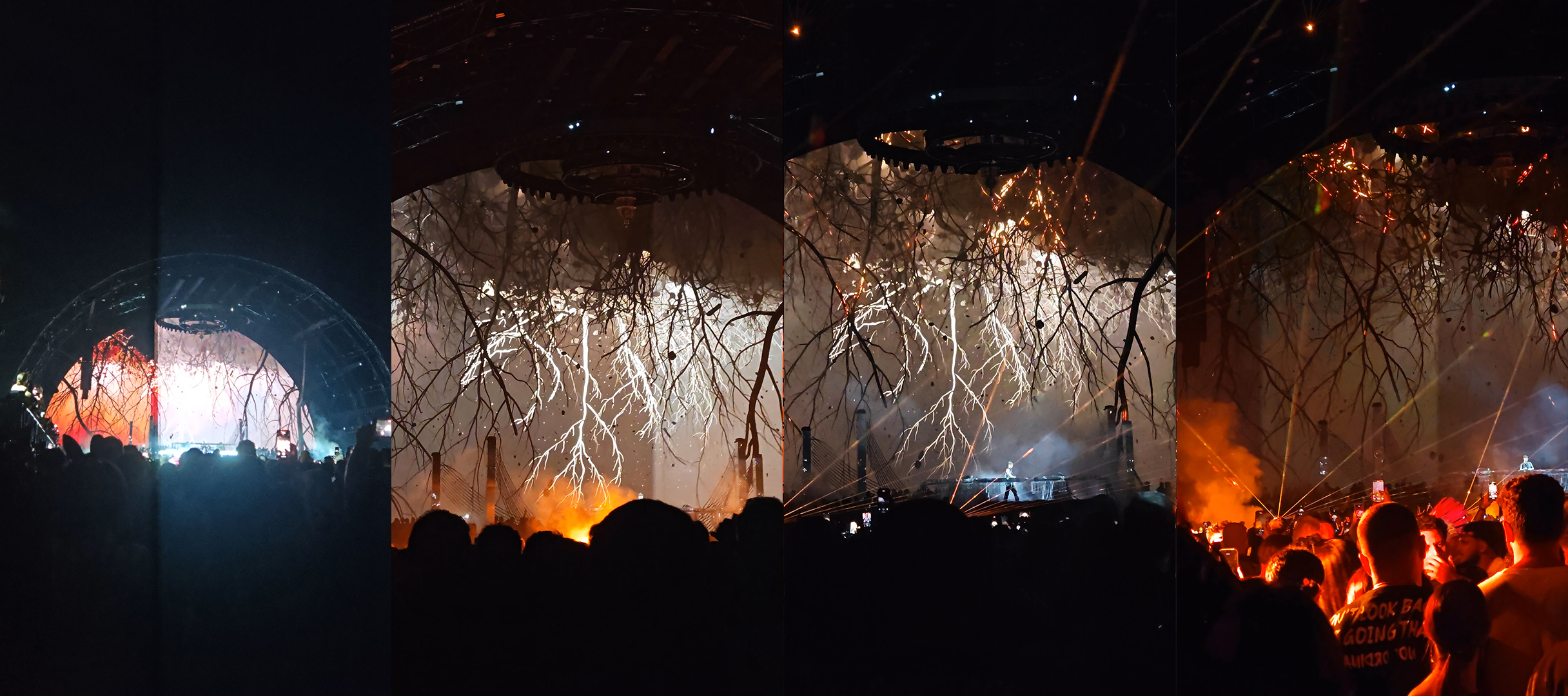

The night in Dubai was framed by a premise that sounds almost heretical in dance music. Here, light mattered more than sound. That idea does not diminish the music. It reveals the artistic logic of Anyma, the project conceived by Matteo Milleri, who grew up inside the language of clubs and festivals and then stepped beyond it. With Anyma he writes music that behaves like cinema and he treats imagery like a lead instrument. In his world the rig is not an accessory but a score. Color temperature becomes harmony, beam geometry becomes phrasing, pixel mapped surfaces become orchestration, and dimmer curves become breath. Timecode provides the spine while live faders keep the skin warm. Haze density is managed like a paint medium so that thin white shafts can read as calligraphy and full venue washes can feel like architecture. Angles are chosen as a cinematographer would choose lenses, with low side light to sculpt a silhouette and high back light to turn a figure into myth. Palettes are disciplined rather than loud, with cool whites and deep blues and measured magentas carrying emotional meaning that the audience reads without needing a glossary. This is the path that led to Dubai Harbour in October, where LEDs, lasers and motion graphics stood shoulder to shoulder with drums and synths and where the lighting design did more than decorate the drops. It carried narrative, controlled scale, protected sightlines, respected safety, and set the emotional key of each scene so completely that the music could sit inside it like a voice inside a well tuned instrument.

Anyma began as the laboratory for a producer already known for architectural sound. Matteo made his name as half of Tale Of Us, sculpting melancholic, widescreen tracks that turned breakdowns into breathing rooms. With Anyma he pushed deeper into narrative form, releasing a body of work across a sequence that listeners casually call the Genesys era. You can hear the continuity in the way chords are voiced and how kicks are placed slightly behind the grid to give the groove a human pull. You can also hear a difference. Anyma tracks move with a filmmaker’s sense of pacing. There is often a patient opening image set by soft pads and a motif that emerges like an object in a beam of light. Then a scene change, sometimes a sudden one, that reveals a darker texture or a chiming arpeggio in counterpoint. Even the most club focused records feel storyboarded.

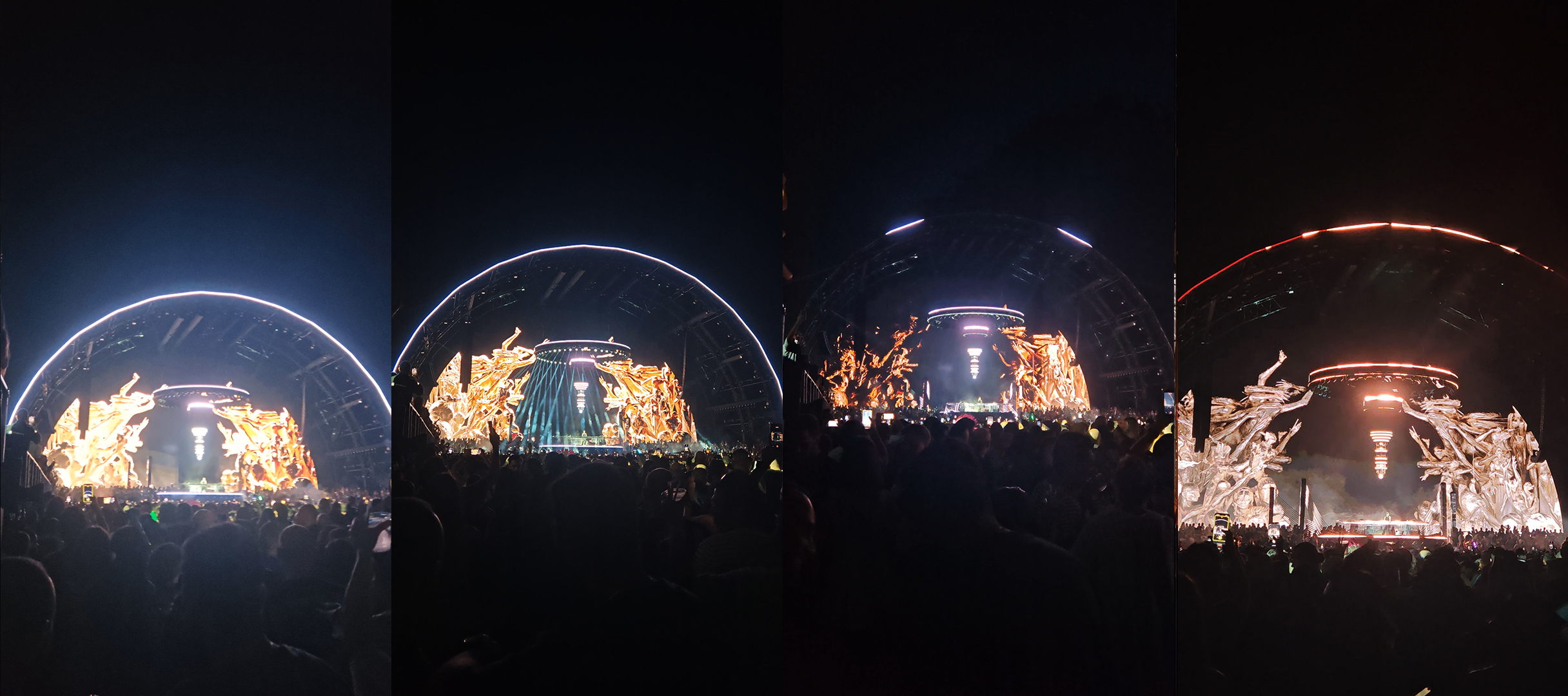

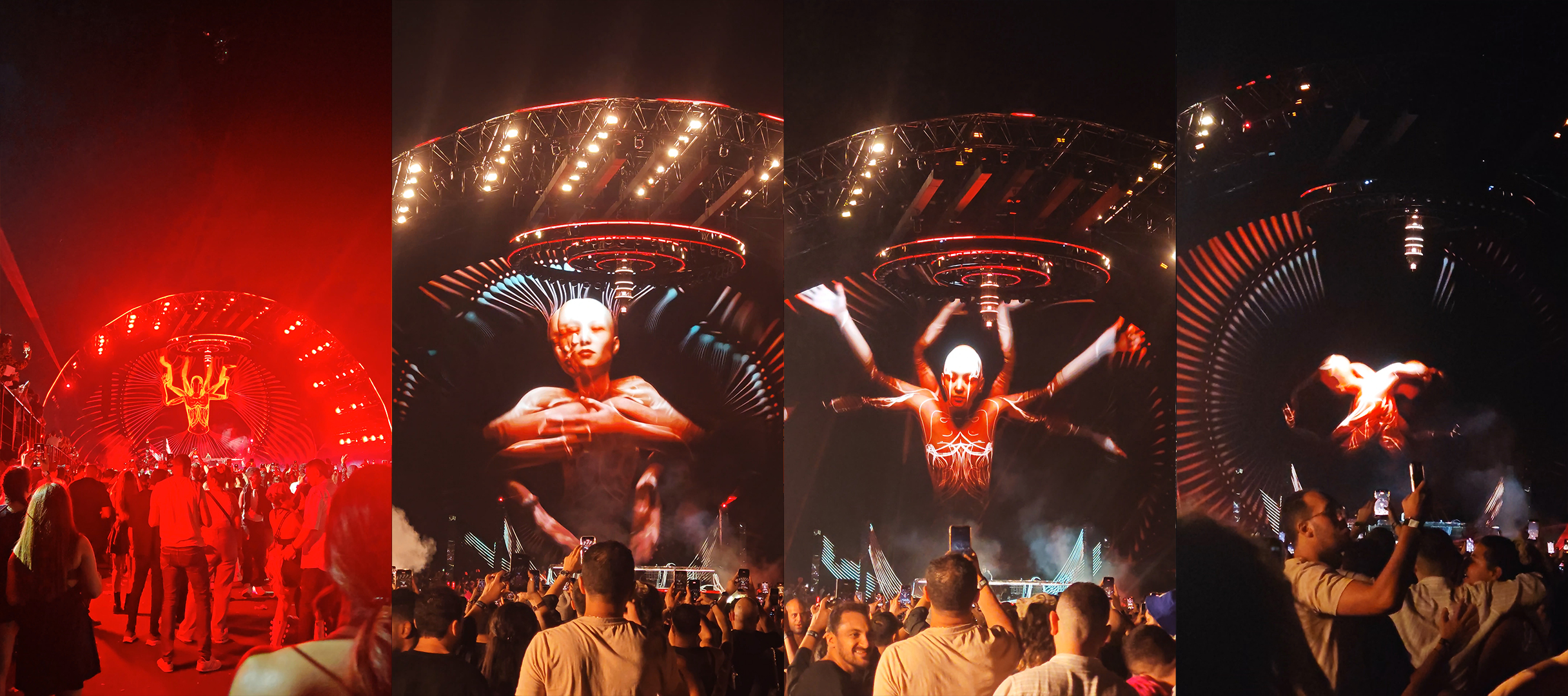

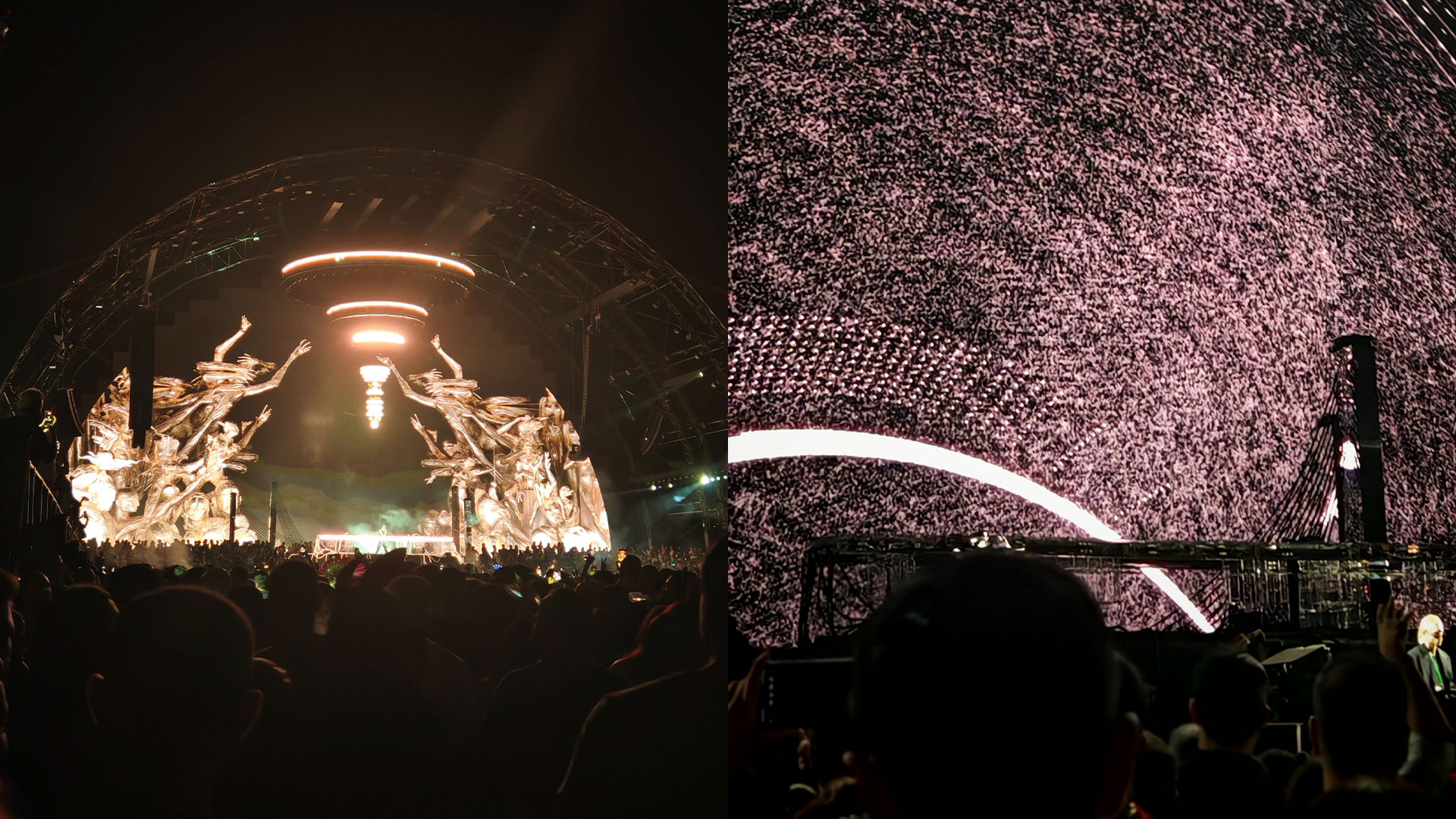

That storyboard is not just a metaphor. Anyma collaborates closely with designers and visual technologists who treat each newly finished piece of music as a script. The visual language that surrounds the songs is full of recurring figures and symbols. There are luminous bodies that feel human but not quite, mechanical flora and fauna, rings that open like portals, and objects that behave as if gravity were an aesthetic choice rather than a law. These motifs are not just album art or screensaver loops. They are time coded to the music, built to breathe and break with the drums, and they are designed to be legible from a field away on monumental screens. This practice turned the project into a meeting point for disciplines. An Anyma show is the place where motion design, lighting design, stagecraft and live mixing collapse into one instrument in the hands of a single performer.

For many listeners the gateway track was Eternity, a collaboration that captured the emotional sweet spot that defines Anyma. It marries a simple repeating figure with a vocal that feels like a plea sent upward into a vast room. The public learned quickly that the visual counterpart to Eternity features a figure suspended between becoming and dissolving, lit as if by a halo that keeps changing shape. That pairing of sound and image became a brand signifier, but it also became a function. Anywhere Eternity lights up a screen, the crowd understands that this is a world with its own physics, a narrative where the visuals do not merely decorate the drop. They announce it. The same applies to later material. Songs may be released as standalone tracks, but the show treats them like chapters. The images are the book’s typography.

This approach puts unusual weight on lighting. Not simply more lights, or brighter lights, but cues that are thought of as editorial marks. A row of strobes can punctuate a measure like commas. A cluster of moving heads can take on the job of a camera, zooming and reframing the audience’s attention. Low angle floods can sculpt the performer into silhouette so that the screen becomes the protagonist for a few bars, then a tight white spot returns the body onstage to presence. Color is used as harmony rather than paint. A switch from cold white to sodium amber is not a decoration, it is a modulation. These decisions are not accidental on the night. They are written and rehearsed. The programming merges with the music file like two layers in the same session.

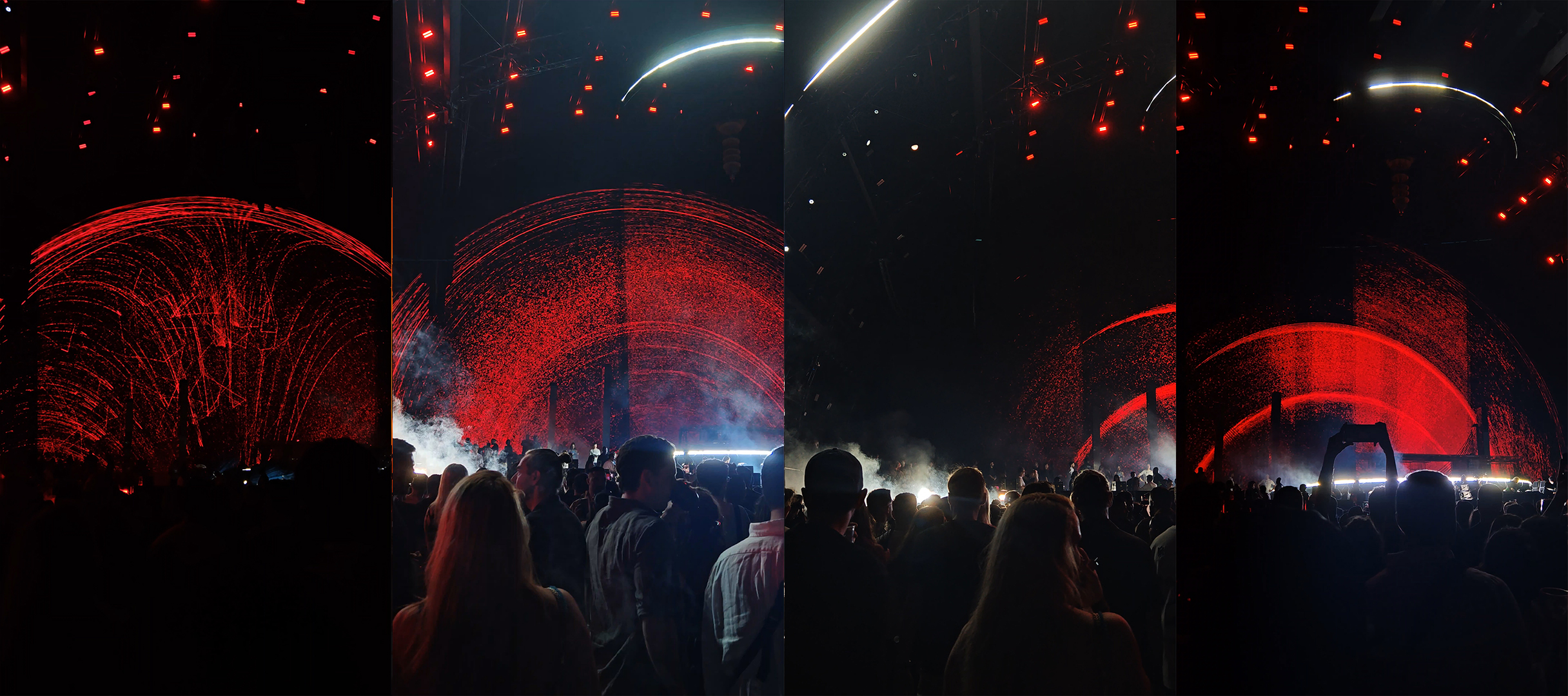

This is why Anyma’s shows flourish on large format stages. The bigger the canvas the more precise the meaning of a lighting change can be. The Dubai Harbour setting supplied scale in every dimension. The open air site faces the water and the skyline, which means the first dusk cues have two horizons to bounce off. It also means wind, humidity and sea air, elements that lighting designers must respect. When daylight slides into the blue hour, you can execute low intensity looks that would be lost in full daylight and too harsh in pitch dark. By night the space is wide enough for spatial gestures. A horizontal laser can read like a ground plane. A ceiling of beams can become a vault. The venue’s permanent infrastructure functions like a skeleton onto which touring shows can bolt custom ribs.

In the months leading up to October, the Dubai date was presented as a debut for a new iteration of Anyma’s concert concept. The term that circulated around the announcement was Quantum, a name that suits the sense of discontinuity and leap that the visuals often enact. Without getting hung up on titles, what matters is the promise the show makes. It promises that the audiovisual language has evolved again and will be delivered at a level you would expect from a major season opener. It promises that the soundtrack will be a blend of signature material and newer edits that fit the larger arc. It promises that the journey will be underwritten by production that does not treat light as an afterthought, but as the carrier of the story.

The night itself was run like a miniature festival with an early opening and a build that respected listener stamina. Support DJs steeped the space in the melodic and techno palette that Anyma’s audience recognizes, calibrating dynamics while keeping the top of the spectrum uncluttered so that later, when the headliner’s show file arrived with full bandwidth, the difference would feel meaningful. By the time the headline slot began, the site was a field of anticipation with phones lowered rather than raised, which is often the sign that a crowd expects to be surprised and wants both hands free.

Anyma’s entrance in Dubai was a study in restraint. The opening minutes let the sound system announce itself with space rather than brute force. The lighting followed suit. A cool wash set the stage at a low level, and the first movements belonged to the screens. Only after the eye had a point to settle on did the beams begin to paint. When the drums thickened, the lighting stepped forward with carefully written accents so that every four or eight bars something shifted, never randomly, each shift a reason to breathe in or out. This made the first big lift feel earned. You could sense how the lighting programming had been plotted like a camera script with a sequence of wide shots, mediums and close ups, even though no literal camera was involved. The rig itself performed the edits.

Once the show reached cruise altitude the conversation between sound and light held the room. Dubai’s stage allowed the screen architecture to read cleanly from back to front. You could see deep into the visual world. The moving heads acted like a chorus that framed these worlds, sometimes in symmetry, sometimes broken into asymmetrical groups to keep the eye dancing. Lasers were used sparingly at first, then with decisive force in sections where the music needed a plane drawn across the audience like a lid. When hits from the catalogue arrived, the lighting design did not simply go brighter. It went more articulate. Palettes narrowed to two or three colors for entire passages, which meant the smallest addition of a complementary hue felt seismic. The crowd learned that when a saturated blue was suddenly interrupted by a thin line of white, a new chapter was opening.

The sound at Dubai Harbour carried the weight Anyma’s low end requires. Kick and sub felt tall rather than just loud, which is a psychoacoustic way of saying that the energy occupied vertical space in your body rather than smearing across the floor. This matters to lighting because it gives the programmer a stable grid to write against. When the bass notes are round and even, a precise strobe rate can ride them without flaming. When the midrange is clean, a beam chaser can be timed to the arpeggios without washing out the screen content behind it. Throughout the set you could hear the mix engineer solving for clarity not just in sound, but in the way sound would give light a place to sit.

There were sections where Anyma ceded the ledge to the imagery entirely. In one long breakdown an animated figure appeared that seemed equal parts human and mineral. The lighting fell away to a hush, leaving the figure to grow across the screen without glare. The rush of the crowd was not for a drop. It was for recognition. People knew the figure and what it meant for the musical phrase that followed. When the drums returned, the lighting did not jump back to the previous level. It climbed by measured steps, allowing the screen to keep telling the story while the beams restored the sense of immersion. In this way the show made the audience complicit in the pacing. There was time to be still and time to explode.

The open air site shaped other decisions. Wind across the harbour can make haze unpredictable, and haze is the invisible canvas on which beams are drawn. The team compensated by choosing moments where haze density could build between gusts, then unleashing geometric beam looks while the air remained saturated. When the wind shifted, the show shifted to screen forward scenes and low angle wash that reads without haze. The timing of these alternations was musical. It let the environment become part of the composition rather than an obstacle. The skyline became an unplanned collaborator too. When deep ambers and warm whites were used, the towers around the harbour appeared as silhouettes against the beam grid, which lent an architectural undertone to the trance of the middle third.

One of the more striking achievements of the Dubai performance was how human it felt despite the machinery at work. Anyma spent long passages as a silhouette, a figure in front of the world he had brought to life, and then would step back into the light just enough to remind the crowd that there was a person guiding the sequence. That balance matters because it keeps the show from becoming a film you watch rather than a concert you attend. The gestures of the performer, tiny on such a large stage, were amplified by lighting choices that knew when to isolate and when to dissolve. A narrow key from high front at low intensity could turn a head nod into a punctuation mark visible from the back rail. A backline blackout with a single side light could turn a fader move into a revelation.

By the final quarter of the set, the grammar of the show was fully absorbed. The audience understood that a particular shade of cyan prefaced a leap into metallic gray. They knew that when the strobes fell into a two on, two off cadence, a motif was about to return. They knew that a sudden silence would never be empty, that a single white beam might arrive and hang in space like a question mark. These patterns are the signature of a show that takes lighting seriously as narrative rather than noise. They also prepared us for a second act that could climb even higher into the story of light.

Dubai’s opening night functioned as a proving ground. It proved that Anyma’s thesis carries at stadium scale. It proved that you can stage an electronic concert where the most important creative decisions are solved in light first, and sound serves that score without losing its power. It proved that a city used to spectacle can still be surprised by precision. This is why the phrase a concert where light mattered more than sound is not provocation but description. The set worked because its lighting design thought like a composer and behaved like a camera, because it gave the visuals room to speak and disciplined the music to act as a partner rather than a tyrant. The result was not cold. It was emotional in a way that only careful planning can achieve.

All of this sets the stage for a deeper dive. In the next section we will concentrate entirely on the lighting architecture of the Dubai show. We will map the rig in plain language, walk through the programming philosophy scene by scene, and consider how color theory, beam geometry and timing were used to produce meaning. We will isolate moments when the visuals led and moments when the lights took the lead, and we will look at how audience psychology was shaped by those choices. We will treat cues as sentences, palettes as harmonies and strobe rates as rhythms, because that is how the show invited us to read it. Here in Dubai, on a harbour lit by a thousand sources including the city itself, Anyma proved that light can be the protagonist of a night and that sound, given a generous heart, is happiest playing a perfect supporting role.

What stayed with me after Dubai was not only the memory of songs, but the feeling that the room had been written in light. The previous section sketched how the show balanced images, sound and the personality of an artist who treats the stage like a storyboard. Now we can slow down and look at the craft that made that balance possible. We can read the rig the way an editor reads a score, we can trace the color logic scene by scene, and we can place those choices inside a lineage that runs from the Light and Space movement to contemporary arena production. This is a report for people who design with photons. It asks how Anyma’s concert language turns lighting from a layer into the lead.

Start with the basic grammar. The show treats light as a time based instrument, which means the first questions are about tempo and subdivision rather than brightness. A great many passages sit near the familiar dance tempo where a quarter note lasts about half a second. That gives the programmer a stable grid from which to derive strobe rates, chaser speeds and oscillation periods. When a cue paces the eye at eighth notes, the brain experiences anticipation. When it drops to whole notes, the brain experiences release. The show’s programmers use these relations with the same discipline that a drummer uses ghost notes. Fans often describe the music as cinematic. In truth the lighting is what gives the music its sense of edit points. A sweep that rises over eight bars is a tracking shot. A cluster of tight white hits on one and three is a hard cut.

Once the time grid is established, the question becomes where light sits in space. The Dubai Harbour site gave the team real depth from upstage LED walls to downstage truss to audience truss lines. The show places three kinds of space in conversation. There is screen space where rendered worlds and figures live. There is beam space where volumetric looks carve the air. There is human space where the performer’s body and the first lines of the crowd need definition and warmth. The design respects all three. The logic is simple and strong. When screen space drives the narrative the designers drain beam space to a low glow or pull it entirely and they keep human space in silhouette. When beam space carries energy the screens go darker or shift to high contrast motifs with negative space so haze drawn geometry remains legible. When the night wants intimacy human space gets a soft key and low color contrast and everything else falls away. It reads as a conversation rather than a fight.

The tools that make this conversation legible are not new, but they are used with unusual restraint. Narrow aperture LED beams paint invisible planes of haze. Hybrid spots provide the crisp punctuation marks of a gobo or a prism split when the music requires ornament. Linear battens pixel map into waves that roll across the truss like notation. From the console side you can sense a grandMA style show file that is time coded for macro structure but still leaves faders for color and intensity rides so that the operator can respond to audience energy and atmospheric changes. The timecode is the spine, not the cage. This is how the show keeps the impression of life while remaining perfectly in sync with the dense edits living on the video server.

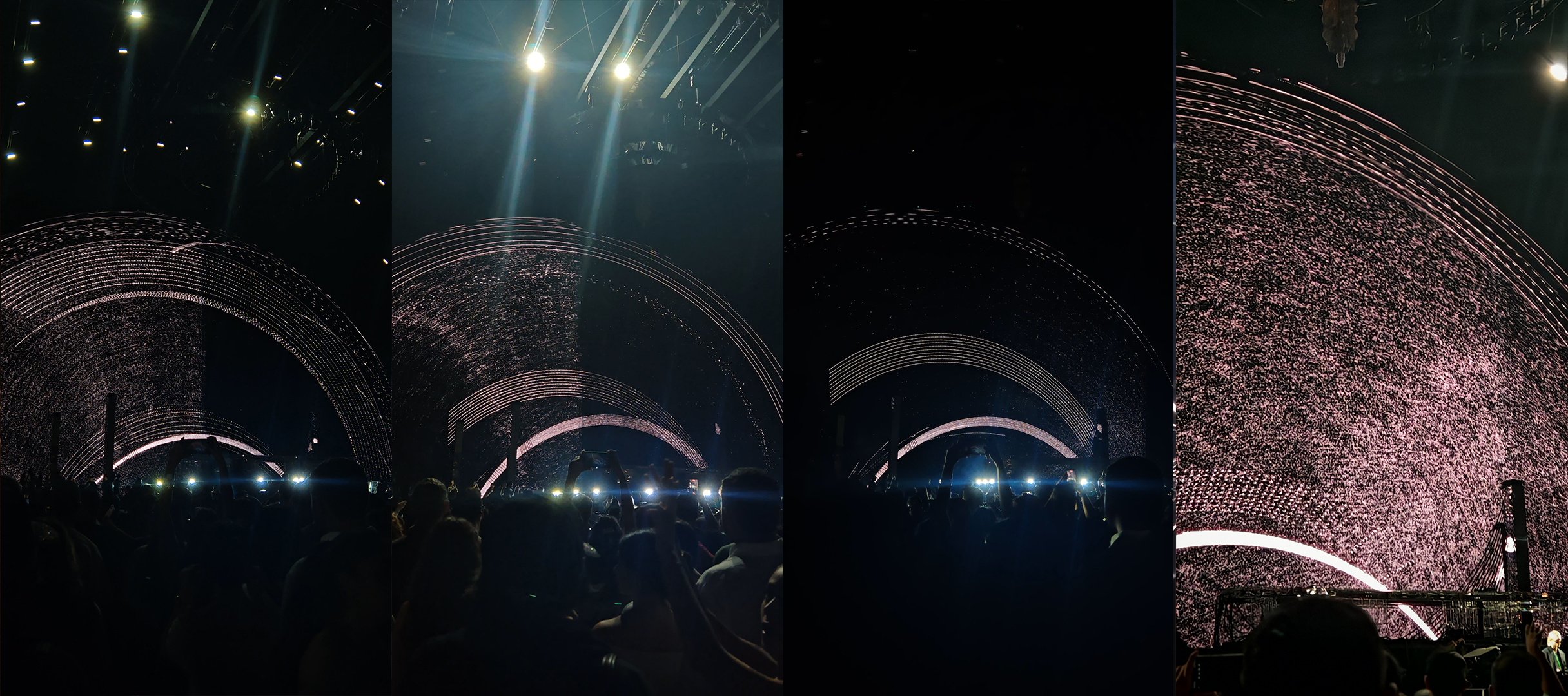

Color deserves its own chapter because the show uses color as harmony rather than decoration. The palette is anchored by a set of archetypes that come straight out of both physics and culture. Cold white around six thousand Kelvin functions as moonlight and moral clarity. Warm white around two thousand two hundred Kelvin functions as memory and human closeness because it touches the hue of fire and the sodium glow of old street lamps. Cyan and deep blue stand in for ocean and night sky. Magenta carries the synthetic promise of science fiction that cinema has taught us to read since the era of neon. The show narrows to duos and trios of these colors a surprising amount of the time. This is classic Itten and Albers. Limit the palette and your smallest shift feels symphonic.

The cultural references are not vague mood board citations. They are legible to anyone who has spent time with the Light and Space artists of the American West Coast. James Turrell taught generations to feel how slow color changes alter our sense of time and how the eye erases edges when luminance is balanced. Dan Flavin taught us to trust the raw authority of a single hue in a room. Those lessons show up in passages where Anyma’s rig holds a single saturated field for much longer than most EDM shows dare. There are minutes where a deep cerulean owns the space and only a thin white beam draws a vector across it. There are breaks where the entire venue is washed in warm white as if the rig were a candlelit nave and the crowd a congregation. The result is not retro. It is a clear line from art history to show control practice.

The show also borrows from film language in its use of complementary pairs. The magenta and teal duet that dominates modern action cinema appears here in the service of legibility and mood. Skin reads well against teal and metal reads well against magenta, which keeps the performer and the screen objects alive even when the beams are busy. You can see the method in the contrast maps. A teal field with magenta accents invites a white strobe to act like a lightning bolt without polluting the palette. Reverse it and the stage becomes a night street where a neon sign hums. The rig avoids the temptation to throw the entire rainbow at the audience. In an era when RGB fixtures can draw any color, restraint becomes the rarest effect.

Light behaves like matter, so the show treats haze as a fourth instrument. The team manipulates density the way a painter manipulates the tooth of a canvas. High density supports low intensity beams that feel like graphite lines. Low density calls for higher intensity or for deep saturation to keep edges visible. Outdoor wind across the harbour demanded moment by moment adjustments. You could watch how the operator waited for a pocket of stillness to launch a cathedral ceiling of beams that held for a few bars before being retired in favor of screen forward scenes when the breeze returned. The transitions synced to the musical phrasing so the meteorology felt like part of the composition rather than a compromise.

There is also an ethical piece to consider because high powered lasers and extreme strobing can cross a line into harm if misused. The Dubai show was a model of how to push intensity without courting risk. Aerial laser looks were elevated above eye level and never held at a single scan pattern for too long. Strobe sequences lived in musical bursts rather than abusive walls of light. The design respected the neurological limits of the audience while still delivering the shock and awe that a season opener demands. This is a best practice worth stating plainly in a field magazine. Safety is not the enemy of impact. It is the precondition for it.

Meaning in Anyma’s lighting language emerges through repetition of motifs across a set and across shows. A single vertical white shaft often marks the threshold before a new chapter. A halo of warm white from high back that flares and collapses is a signal of transformation. A full field of monochrome blue is a pause for breath. These motifs accumulate force the way leitmotifs do in opera. You do not need to know the backstory to feel their weight. This is why fans who have seen different dates can talk about the show as if it were a narrative. In that narrative, light is the speaker and sound is the score that supports the voice.

There is a long tradition of club lighting that privileges energy over legibility. The Dubai set leaned toward meaning without sacrificing energy. That balance is achieved through careful control of contrast ratios and angles. Front light was used sparingly so that the performer became a silhouette most of the time. Side and back light shaped the figure and gave screens priority. Low angle foot sources appeared during intimate moments so that the face became readable without flattening into a television look. These are theatrical lessons brought into a large scale outdoor environment. The focus is always on how the eye finds hierarchy. Every cue asks the question. What should the audience read first. The answer changes bar to bar.

Rhythm in lighting is more than on off. It is about the duration and the curve of movement. The show’s beam sweeps use sine and triangle waves of movement rather than simple ramps. When a bank of moving heads swings on a sine, the deceleration at the extremes adds grace. When it swings on a triangle, the constant speed feels mechanical and urgent. The programmer chooses between those feelings the way a drummer chooses between swung and straight. Even the fly outs of brightness respect curves. A snap to black is a shock that belongs to specific drops. Elsewhere the decay follows a soft exponential that the eye experiences as breath. This is craft at the level of touch.

Technology makes such touch possible at scale. The integration between lighting console, timecode and media server lets color values and content changes share a timeline rather than fight for attention. Pixel mapped fixtures speak the same language as the LED wall so that a ripple across the screen can echo across the truss in the same millisecond. This is not about gadget worship. It is about removing friction so that artistic decisions can be made at the speed of music. When a crowd feels the show is alive and inevitable at the same time, that is usually what they are feeling the absence of latency between the parts.

Cultural memory sits inside color too. Amber is the color of street nights in Southern Europe where sodium lamps wrote entire cities in sepia. Blues and cyans are the colors of nocturnes from Debussy to Blade Runner. White at six thousand Kelvin is the lab. White at three thousand is the home. Anyma’s palette uses those associations strategically. A long amber scene in Dubai made the harbour feel like a city street brought into the concert. Moments later a cold white transformation turned the same stage into a scientific theater. The crowd does not need to know the numbers to feel the change. The body knows what color temperature means because we have grown up under different kinds of light.

If you wanted a simple diagram of the Dubai set’s color dramaturgy, you could draw a triangle with warm white at one vertex, cold blue at another, and magenta at the third. The show walks the edges and visits the center in careful arcs. When the music needs catharsis the triangle collapses to white and cyan, and the beams become straight lines that define volume like architectural ribs. When the music becomes internal the triangle expands into magenta and deep blue and the beams curl. When the music wants collective joy warm white floods the crowd and the performer’s silhouette reappears in perfect proportion. The map is steady enough to be learned over the course of two hours, yet flexible enough to keep surprise alive.

Comparisons help clarify what is uncommon here. Many large scale electronic shows lean on pyro and constant motion. Anyma’s lighting will freeze. It will hold a single look while the content shifts behind it, allowing the audience to breathe in the story instead of chasing flashes. This is closer to the patience of a Turrell Skyspace than to a festival finale, even though both can live in the same night. Another comparison is to the work of Xenakis and the Philips Pavilion, where light, sound and structure acted as one. The Dubai stage is a modern descendant of that idea. The rigs are more powerful and the control more precise, yet the goal is the same. Create a total artwork where the audience stands inside the score.

For a lighting professional, the most inspiring lesson from Dubai is about authorship. The show asserts that lighting can lead. It shows that when color and movement decisions are made early in the creative process, music and video will follow with ease. It also shows that meaning is a product of limits. Because the palette stays tight and the beam vocabulary remains disciplined, every modulation carries significance. The rig proves that a concert can feel huge without looking busy. It proves that audiences will sit still for a long monochrome scene if the timing is honest and the story clear.

The closing images of the night told that story with the clarity of a thesis statement. The stage stripped back to a field of cool white that lifted the screens into dream distance. One bright shaft found the performer and held for two heartbeats. The drums fell away and returned as a single pulse. Then the field warmed by a few hundred degrees and the crowd felt the floor under its feet again. There was no cheap curtain of sparks, no storm of colors. There was simply a change in temperature and a final breath of haze catching the city lights beyond the harbour. It was enough. In that last minute the show argued that light can carry meaning as directly as language and more directly than volume.

This is why the phrase that opens this report is not a provocation. It is a precise description of how the night worked. It was a concert where light mattered more than sound. Not because the music was weak, but because the music was strong enough to play the role of rhythm section while light took the melody. For a lighting magazine and for the community that builds the night, that is an important evolution. It points toward a future where designers are composers and operators are instrumentalists, where palettes are harmonies and angles are verbs, where the city itself can be folded into the rig as a collaborator. Dubai showed that this future is already here. The audience did not cheer for watts or fixtures or brand names. They cheered for the feeling that the room itself had been written. They left with a memory of color and time. And if they remember the songs, they will remember the light that taught those songs how to speak.